by Alethea Eason

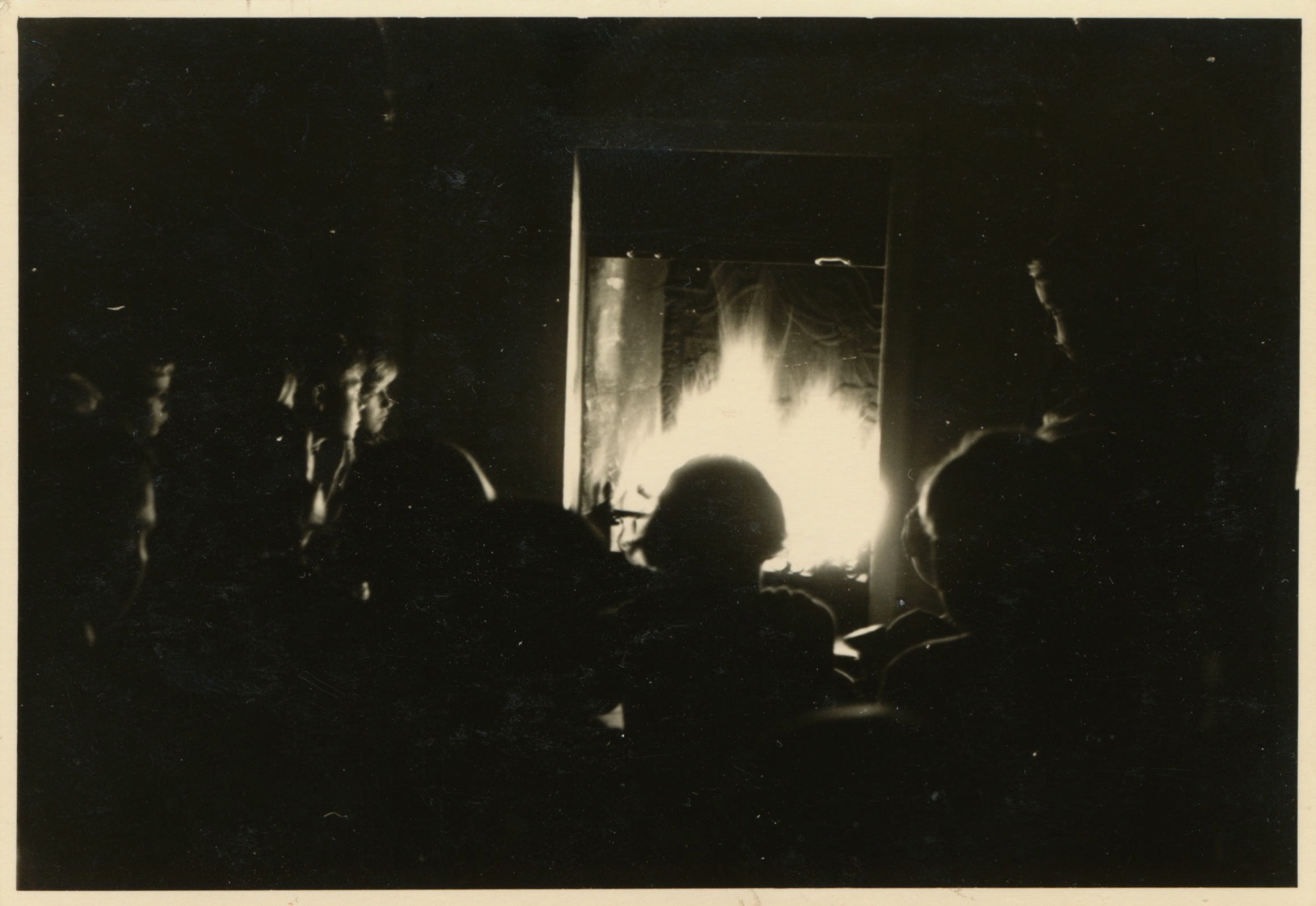

An angel of light came to the night woods, searching for what was unobtainable in his Heaven. He had never ventured to my paradise before and arrived with guardians, though his brothers must have told him not to be afraid. His three holy wolves bared their alabaster fangs as I approached, my Nereid shell opening to woman form. But when I spread my own ribbed wings and beckoned, they whimpered and lay at my feet.

“You are far from home,” I whispered, and kissed his rigid jaw. “How sad there is no sex in your heaven, no fertile soil, no animal flesh.”

The wolves cried for they too were made of light. I sensed their sad longing for the pack, earthly memories of pups licking their faces and the taste of prey on their tongues.

My wings touched his and he sighed. We mated in the aqua sky; starlight shining upon virgin trees, amid a thousand fireflies burning through the ecstasy of their short lives. He now carries my child—angels are like seahorses that way—and has returned to his paradise. I descend to roots and the sweet decay of matter bearing life in a much different way.

Alethea Eason is a writer, artist, and teacher who lives in Northern California. She has written the young-adult novels Hungry (HarperCollins) and Heron’s Path (Spectacle MPG).

Alethea Eason is a writer, artist, and teacher who lives in Northern California. She has written the young-adult novels Hungry (HarperCollins) and Heron’s Path (Spectacle MPG).